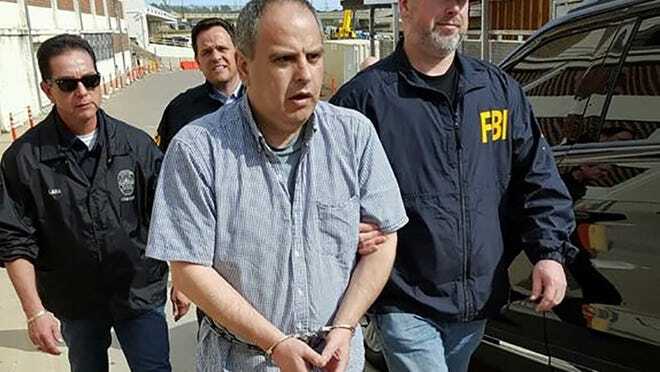

Federal agents with the FBI and Customs and Border Patrol escort Robert Van Wisse at the Texas-Mexico border in Laredo as he is taken into custody in January. Van Wisse sexually assaulted and killed an Austin woman in 1983 but was brought back to the U.S. to face charges after fleeing to Mexico. FBI” data-c-credit=”Austin American-Statesman”

On the January afternoon a 33-year manhunt was about to end, three veteran investigators stood at the Texas-Mexico border waiting for a killer to peacefully surrender and face charges for raping and strangling a woman in a South Austin office complex in 1983.The delicate operation had been a couple of weeks in the making, arranged through a series of high-level meetings between prosecutors, law enforcement and defense attorneys. It hinged on a promise that the accused murderer was ready to face justice and would be catching a bus from Mexico City and travel nearly 12 hours to Laredo to turn himself in.The officers weren’t optimistic a criminal would keep his word — or trade a life of freedom for prison — but after only a few minutes, a nicely dressed man matching age-enhanced photographs walked up, looked them in the eye and quietly said, “I’m Robert Van Wisse.”

“This case had been lingering for so long, and it was emotional in that this family was going to get some closure,” said Austin police cold case Detective J.J. Schmidt.

Van Wisse’s plea Tuesday in Travis County court to 30 years in prison in the death of Laurie Stout marked the culmination of what legal experts say was a highly unusual play by prosecutors that went against traditional practices of when and how to broker a deal with criminals.

Over a period of several weeks that began soon after she took office in January, District Attorney Margaret Moore and her staff engaged in negotiations with Van Wisse (pronounced weesee) through his defense attorney and across international borders to try to convince him to surrender.

Veteran prosecutors say such an approach is rare. Instead, law enforcement officials are usually focused on finding and arresting a fugitive in Mexico or wherever they may flee, and then often going through a lengthy extradition process to have them returned to the United States.

George Dix, a longtime University of Texas law professor, said he’s never heard of a similar plea negotiation. “The most obvious benefit is that you get a defendant to turn himself in instead of what could be the improbability of finding him and getting him into custody,” he said.

“The prosecution normally won’t talk to the representatives of defendants who are not in custody because they don’t want to create a system that rewards people for not submitting themselves for arrest but still have the benefit of negotiating their case,” said John A. Convery, president of the Texas Criminal Defense Lawyers Association.

Moore acknowledged that engaging in a back-and-forth with international fugitives before they are in custody is not common. However, she said she was willing to do so in Stout’s murder because she wanted to bring justice to her family in a case that had lingered more than three decades.

“As a brand new DA, I was confronted with something unusual, but I thought it was the right thing to do,” she said. “The overriding interest was to get him in our custody to face the charges here.”

Perry Minton, who represents Van Wisse, said his client realized once he was on the FBI’s 10 Most Wanted list that detectives were intent on finding him — and probably would. He also believed that surrendering before his arrest could enable him to strike a better deal.

Minton said he also knew it was time to face justice: “He truly did come on his own because if he wanted to move yet again and disappear, he certainly could have,” he said.

Initially ruled out as suspect

The murder of Laurie Stout shook Austin at the time and led to a massive law enforcement effort to find her killer.

According to police accounts, Stout, who owned a janitorial service with her husband, was cleaning an office building on South First Street when Van Wisse attacked and killed her in a men’s bathroom. Investigators said she had been sexually assaulted and strangled with a wire.

Police interviewed people who had been in the office building, including Van Wisse, who was there to register for a class at the University of Texas.

The case remained unsolved a decade until the early 1990s, when an Austin police cold case detective reopened it. He learned that investigators had mistakenly concluded that Van Wisse’s DNA didn’t match that of the killer, but he and other detectives later confirmed that it, in fact, did.

In October 1996, police charged Van Wisse with murder, and police think he fled to Mexico around that time. During the past two decades, investigators said he made a living as a handyman and remarried and had children. Minton said none of them knew Van Wisse killed Stout, and he insists Van Wisse never received financial assistance to remain on the run.

But in Austin, police said they never gave up on finding him.

Schmidt said that investigators in the department’s cold case unit have a mantra: “We don’t ever quit. We don’t ever give up, and on this case, that has been since Day One.”

Last fall, Schmidt, who maintains regular contact with Robert Marcum, a deputy United States marshal, and FBI agent Justin Noble, began an effort to get Van Wisse on the FBI’s 10 Most Wanted list, and authorities in December announced that they were adding him.

That decision led federal officials to put more heat on the case and to begin a more aggressive effort to work with Mexican authorities to find him and bring him to justice.

As investigators established a possible location on Van Wisse, detectives also visited his parents in the Austin area, who informed them that their son might be willing to turn himself in, but indicated he must know his punishment before doing so.

That led to a series of meetings during the first three weeks of January between federal agents, Austin police and Travis County prosecutors.

Minton said when he and fellow attorney Rick Flores met with Moore, he was “absolutely pleased” that it appeared as though “we may have a pathway to resolve this for both sides.”

“Setting up the communication with my client was a risky endeavor,” he said. “I didn’t want to engage in that if they weren’t interested. The manner in which Robert had learned to live his life was such that any communication between him and his attorneys was solely at his discretion and could only be initiated by us through a very involved process.”

Moore said she was willing to forgo any discussions of seeking the death penalty. After all, she noted, Mexican authorities typically will not agree to extradite criminals if they think they will be executed.

But Moore and veteran prosecutor Amy Casner said the more challenging discussion centered on negotiating a plea with a defendant who wasn’t in custody.

She and Casner decided to break from their office procedure and to provide Minton evidence in the case — something that usually happens weeks after a defendant has been arrested and charged. They said they wanted to make sure he had appropriate information to represent and advise his client through long-distance negotiations.

Minton said that in most cases when he is negotiating a plea, defense attorneys retest forensic evidence, interview experts and conduct their own independent investigation to fully represent their clients.

“That was the most difficult thing about this case,” Minton said. “But I was working on a deal based on my client’s wishes.”

After some debate on the strengths of the case, prosecutors and Minton settled on a 30-year sentence for Van Wisse on a murder charge.

“We felt it was reasonable given the circumstances of the case,” Casner said. “And we believed it was in the realm that was reasonable for him to take.”

Seeing is believing

On the day before he turned himself in, Minton alerted investigators and Moore that Van Wisse was riding a bus from interior Mexico to the border.

Schmidt, Noble and Marcum drove to Laredo almost immediately to scope logistics and where they could best meet Van Wisse.

Casner and a fellow prosecutor who also has worked on the case drove to the border that morning in case any legal questions came up during the arrest or transport of Van Wisse back to Austin.

“We were still wondering if this was really going to happen,” Casner said. “I’m a pessimist by nature, but I was optimistic because Perry believed this was going to happen. It was one of those things, ‘I’ll believe it when I see it.’”

In Austin, Moore had already set a meeting with Stout’s daughter to update her on the progress of the case. As she was walking into the meeting, Moore said Casner texted her a photograph of the arrest.

“I got to tell her, ‘We have him. He’s in our custody’,” Moore said. “She looked up with tears in her eyes and said, ‘This couldn’t be a better day. Today is my birthday.’”

On Tuesday, the day of the sentence, Van Wisse surprised many in the courtroom by reading a prepared statement confessing to the killing, but offering no explanation about what happened.

“In one night, I killed an innocent woman and ruined the lives of everyone I love and care about,” he said. “And more importantly, the lives that cared and loved Laurie Stout. And most importantly, I deprived a little girl from ever knowing her mother.”

Daile Stout, Laurie’s Stout’s daughter, sat in the jury box next to a victim’s counselor.

Stout said a 30-year sentence isn’t adequate for Van Wisse’s crime, but that she understands the complexities of the case and why prosecutors settled on that sentence.

Most importantly, she said, she’s pleased Van Wisse is finally facing justice.

“It’s been something that has been difficult for my family to deal with,” she said. “It’s some closure, where I don’t finally have to be left to wonder if he was out there doing it to other people. Knowing that he is behind bars takes a huge weight off.”